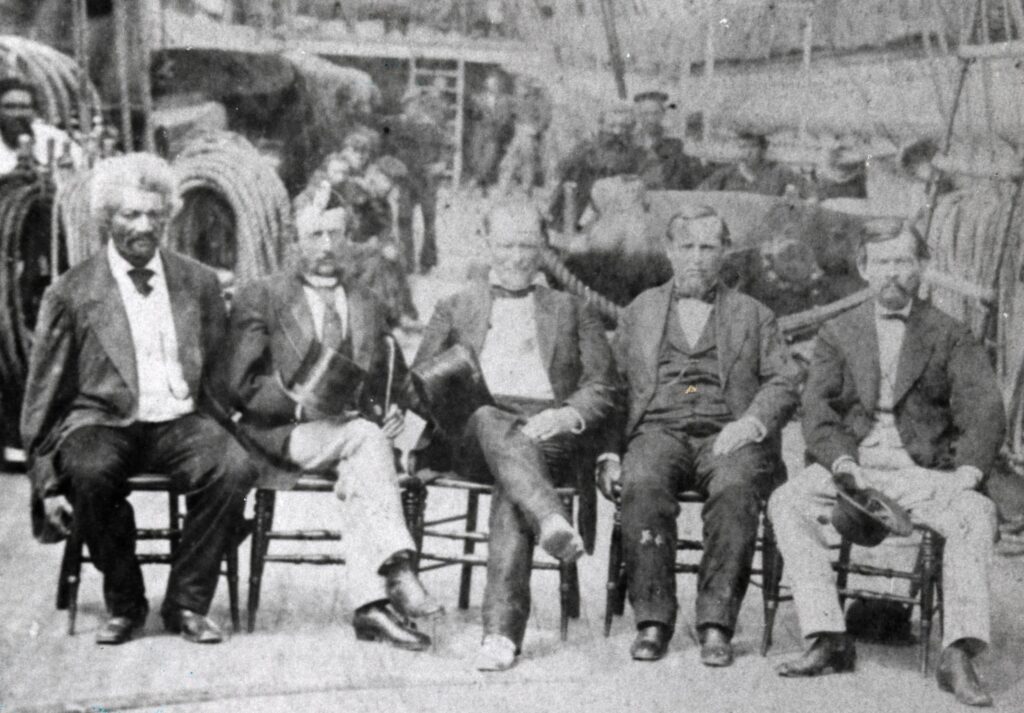

Frederick Douglass and the Haiti Commission on USS Tennessee in Key West

I have read Frederick Douglass’s “What, to the Slave, is the Fourth of July?” many times. There have even been several public readings of it in New Bedford where Douglass lived for a time. I knew Douglass had been an ambassador to Haiti but had no idea that after a long life like his he would endorse American exceptionalism and a belligerent foreign policy. An article in Boston Review by historian Peter James Hudson about Douglass’s ambassadorship in Haiti shows Douglass’s very conflicted views of American Empire:

“When it came to U.S. foreign policy goals, Douglass thought U.S. imperialism was beneficial and believed in the righteous, exceptional character of U.S. power. Indeed, Douglass was more than sympathetic to U.S. expansion and the ‘extension of American power and influence’ in the Caribbean and elsewhere. He had supported the annexation of Santo Domingo in the 1870s and applauded attempts to secure the Dominican Republic’s Samana Bay by the United States for military purposes. Douglass lashed out at those who saw him as somehow subverting U.S. foreign policy goals, stating that he had understood the importance of U.S. dominance in the Caribbean long before his critics ‘were in their petticoats.’

But Douglass was also aware of the moral limitations of U.S. exceptionalism and cautioned against its abuse—especially against countries such as Haiti that had neither the economic nor the military resources to easily withstand U.S. pressure. His experiences as ambassador to Haiti served as a lesson to him in this regard. ‘Is a weakness of a nation a reason for our robbing it?’ Douglass asked. ‘Are we to take advantage, not only of its weakness, but of its fears? Are we to wring from it by dread of our power what we cannot obtain by appeals to its justice and reason?’“

Douglass will always be on my list of inspiring American heroes. But it just goes to show that even the bravest and most principled among us can run aground because of an insufficient understanding of a global phenomenon. And this is precisely where a Marxist analysis of imperialism is useful.

To some, unfeeling, cold and clinical, reviled by all sorts of enemies, especially our own government, Marxism may not invoke the moral outrage of a towering figure like Douglass. But it does carefully and clinically analyze the goals and strategies of imperialism within the context of Capitalism’s insatiable plunder of the natural world and its exploitation of human beings across the globe: in short, the billionaires’ class war on the rest of humanity.

Morality may propel us to change the world; but to do that we must step beyond moral outrage into an understanding of how so many of the ills of society — including poverty, war, genocide, and environmental collapse — are a direct consequence of Capitalism. And then we must unite to decisively end it. Only then can we actually create a world that works for everyone, not merely the current owners.

Postscript

I got some pushback on this article from liberal friends. Of course, Douglass will always be an American hero because he motivated the Abolition movement, without which we might still have slavery in the United States. My intention was not to take potshots at the man or his legacy.

However, almost as soon as the Monroe Doctrine was enunciated in 1823, everybody from the old Federalists to the Abolitionists to even Southern Capitalists found something to dislike about American imperialism. The prime objection was that this would sour relations with Europe, upon which the American economy heavily depended.

Douglass was ambassador to Haiti from 1889 to 1891 and died 4 years later. If he had lived another few years, who knows? He too might have joined the Anti-Imperialist Society, which was founded to oppose American empire in the Caribbean and Latin America. Of course Douglass had qualms about the U.S. throwing its weight around so freely at brown and black people. But when he died at the age of 77 he probably didn’t have much more fight left in him.

So, while I don’t judge Douglass for not seeing as far as some of his younger contemporaries, there had been opposition to U.S. imperialism for almost 60 years by the time he became ambassador. Douglass wrote about the Paris Commune in his newspaper, the “New National Era.” He knew of, and corresponded with, Karl Marx and wrote about Marx’s International Workmen’s Association in the “Era.” He just didn’t like it all that much.

Douglass was suspicious of unions and strikes, remained focused on racial justice, the one thing that had defined his entire life, and not in militant working class solidarity. Today Douglass would probably be a member of the Black Caucus but not the Progressive Caucus, and certainly not a radical socialist.

As with anyone who has left an indelible mark on history, it remains for others to stand on Douglass’s shoulders.

Comments are closed.